Every day, you likely face some kind of conflict.

At least I do.

Luckily for me, it’s usually not the kind of conflict that will get me killed. Instead, I deal with more social conflicts than anything – with coworkers and with family and friends.

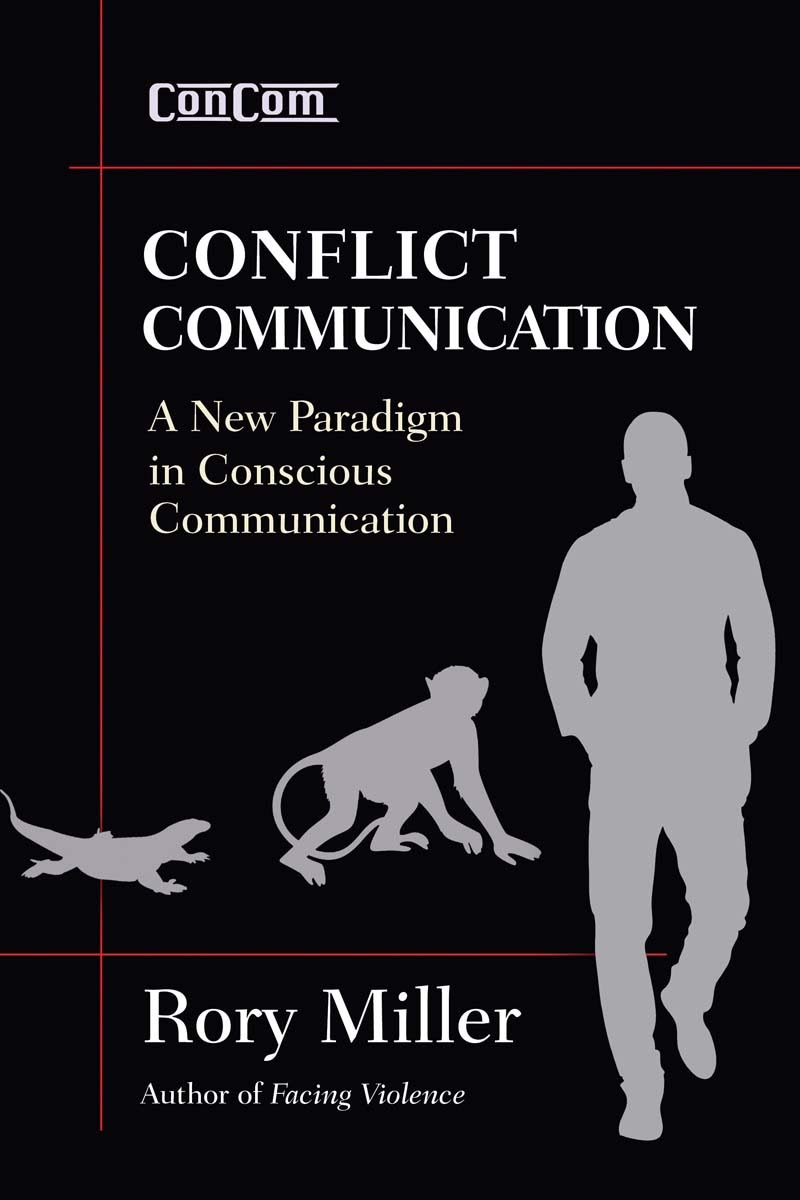

You might be thinking this is a martial arts book, but it’s really not. It’s actually listed under the categories of social science and violence in society.

You might be thinking this is a martial arts book, but it’s really not. It’s actually listed under the categories of social science and violence in society.

In it, he talks about what he calls the three brains.

The first brain is the lizard brain, and it deals with survival issues. Miller describes a cop who continually tells a suspect to drop the weapon despite already knowing he’s going to shoot. In less lethal matters, he talks about athletes being “in the zone.” This brain has more to do with habit and rituals. For example, when you go to the grocery store, the cashier will likely ask you how you are doing and whether you found everything okay. To me, it’s less genuine interest and more of a script.

The second brain is the monkey brain, and it corresponds to emotions. Miller argues, and most people’s personal experience would say, that “most of the conflict we experience comes from this level.” Monkeys fear being cast out of the tribe, he says, because it was akin to being sentenced to a slow and lonely death. Soldiers should fear death more than being laughed at. Otherwise, they probably won’t make for good soldiers.

Finally, there is the human brain. The human brain is thoughtful and rational when it has the right information, but Miller points out that it is slow to gather evidence and weigh the options. Usually, he says, one of the other sections of the brain has a decision ready before the human brain fully explores it.

Miller discusses scripts at length. In the example I provided about the grocery store, it will usually go something like this:

Cashier: “Hi, how are you?”

You: “Good. How are you?”

Cashier: “I’m good, thanks. Did you find everything okay?”

You: “Yeah.”

And the person rings up your groceries and you go along. Maybe he or she will talk to you about the weather because it affects all of us. Or maybe a holiday or sporting event such as the Super Bowl.

You’ll follow the script just to get through. Very rarely, I’d imagine, would a person being checked out at the store say, “My day has gone terrible. A big project I was working on didn’t go as well as expected, and now I’m feeling pressure from both my client and my boss to make the client happy.”

One of the biggest challenges in scripts is that we don’t listen. You know how that store script is going to go.

Miller recommends active listening, in which you essentially take a few seconds to really listen and understand the point the other person is trying to get across to you. I’ve noticed this myself. Instead of thinking about what your supervisor is telling you, you’re thinking about the rebuttal you’re going to give, or the point you want to get across, but you’re not listening to the issue at hand.

For as much value as I place on communication, I dog-eared several pages in this book, certain I’ll need to refer to them again someday.

Note: I received a free copy of this book to review from YMAA.